It is hard not to stare. At the end of a dirt track, deep in the Thai jungle, a group of women sit in the shade, fingering the coils of brass which snake tightly around their unnaturally long, giraffe-like necks.

"It's incredible," says a Canadian tourist, snapping away with his camera, as the women pose - heads bobbing stiffly far above their shoulders - and try to sell him a few souvenirs from the doorsteps of their bamboo huts.

For years the prospect of visiting one of three "long-necked" Kayan villages in this remote corner of north-western Thailand, close to the Burmese border, has been a major lure for foreign tourists.

In return, the visitors have helped to provide a very modest income for the Kayan women and their families, who are all refugees from Burma.

Boycott?

But in a dramatic intervention, the United Nations is now talking of the need for a tourism boycott, amid allegations that the Kayan are being trapped in a "human zoo".

The United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) says that for the past two years, the Thai authorities have refused to allow a group of 20 Kayan to leave the country, despite firm offers to resettle them in Finland and New Zealand.

The suspicion is that the women are being kept in Thailand because of the central role they play in the local tourism industry.

"We don't understand why these 20 are not allowed to start new lives," said the UNHCR's regional spokeswoman, Kitty McKinsey.

"The Thai authorities are treating them in a special way," she argued, pointing out that some 20,000 other Burmese refugees had recently been allowed to move to third countries.

"It's absolutely a human zoo," she said. "One solution is for tourists to stop going."

At the centre of this increasingly heated dispute is a quietly determined 23-year-old woman called Zember, who has proudly worn her tribe's traditional neck rings since she was five.

Zember and her family fled their home in the hills of eastern Burma 18 years ago. Her mother, Mu Pao, remembers government troops raiding their village and taking the men away by force to work as porters.

Like tens of thousands of people, the Kayan headed for the Thai border. But instead of being kept with the other refugees, the "long-necked" families were put in a separate compound a few yards from the official camp.

Since then, the ethnic conflicts inside Burma have raged on, and the Kayan community in Thailand has swelled to about 500.

"At least we're safe here and we can earn some money," said Mu Pao. Each tourist pays a 250 baht (US$8; £4) entrance fee.

Better deal

Other older women in the village agreed that, with little hope of ever returning to Burma, earning 1500 baht a month to be stared at by tourists was an acceptable deal.

But in 2005, a far better deal emerged. The UNHCR began offering permanent resettlement abroad to the many thousands of refugees still living in the area.

Many of the Kayan applied, and Zember and her family were quickly told they'd been accepted.

"I was so happy," said Zember. "They tell me a house is already waiting for us in New Zealand."

For the past two years, however, the Thai authorities have refused to sign the paperwork needed for Zember and 19 others to leave the country.

"Actually they aren't refugees," said Wachira Chotirosseranee, the deputy district officer and refugee camp commander, who insisted this was a purely bureaucratic matter with no connection to the local tourism industry.

"According to the regulations, you have to live inside the refugee camp. They don't meet the criteria."

The Thai authorities argue that the Kayan are economic migrants who earn a good living from the tourist trade and have chosen to settle outside the refugee camps.

"They absolutely are refugees," said the UNHCR's Kitty McKinsey. "It comes as a great surprise that the Thai authorities are criticising them for living outside the camps, when it was the Thai authorities who wanted them to live (outside)."

In frustration, and as an act of protest, Zember has now taken off her neck rings. "It felt uncomfortable at first," she said, rubbing her throat.

Over the years, the rings push the women's shoulders and ribs down, making their necks appear stretched.

"Because of my rings I have suffered many problems," she said. "I wear them not for tourists. I wear them for tradition... Now I feel like a prisoner."

Fantasy world

Warmly Welcome To Fantasy World & Relax For A While!

JESUS LOVES U.

Season's greeting songs

The Lord's Prayer

Gospel Songs

In my mind

We Are The World

Piano Relaxing

Golden Oldies

Warmly Welcome!

Weather

Myanmar Flag

Map of Burma(Myanmar)

World Map

Around the world.

ABOUT ME

Myspace Icons

Candy Bar Dolls Icons

Categories

- Appreciation (1)

- Cartoon (2)

- Child News (6)

- Definations (5)

- Feature Story (2)

- Festival (1)

- Fun (3)

- General (16)

- Gospel (6)

- Greeting (1)

- Health (12)

- Jokes (11)

- Love descriptions (12)

- Love story (2)

- Miscellanies (5)

- Music (8)

- Novel (1)

- Photos (22)

- Poems (2)

- Proverbs (5)

- Quotes (2)

- Season's greeting (3)

- Signs (1)

- Special events (20)

- Youth (2)

Archives

- Aug 13 (2)

- Jul 14 (1)

- Jun 08 (2)

- May 22 (2)

- May 06 (4)

- Mar 27 (1)

- Mar 24 (2)

- Mar 14 (1)

- Mar 11 (2)

- Feb 17 (1)

- Jan 23 (1)

- Jan 15 (17)

- Jan 02 (1)

- Dec 19 (9)

- Dec 16 (1)

- Nov 20 (1)

- Nov 18 (2)

- Nov 12 (7)

- Nov 10 (1)

- Oct 29 (1)

- Oct 25 (2)

- Oct 22 (6)

- Oct 21 (2)

- Oct 20 (1)

- Oct 16 (1)

- Oct 15 (5)

- Oct 05 (3)

- Sep 25 (3)

- Sep 11 (1)

- Sep 04 (2)

- Aug 28 (3)

- Aug 26 (1)

- Aug 19 (1)

- Aug 16 (1)

- Aug 12 (2)

- Aug 05 (1)

- Jul 31 (1)

- Jul 20 (3)

- Jul 16 (1)

- Jul 15 (1)

- Jul 10 (5)

- Jun 24 (2)

- Jun 15 (1)

- Jun 13 (1)

- Jun 06 (1)

- Jun 05 (2)

- Jun 04 (4)

- May 27 (1)

- May 26 (1)

- May 22 (1)

- May 20 (1)

- May 17 (1)

- May 16 (1)

- May 13 (1)

- May 11 (15)

- May 10 (3)

- May 06 (11)

- May 04 (1)

- Apr 23 (3)

- Apr 22 (1)

- Apr 21 (1)

- Apr 17 (2)

- Apr 12 (1)

- Apr 09 (3)

- Mar 28 (1)

- Mar 23 (4)

- Mar 15 (1)

- Mar 14 (2)

- Mar 08 (13)

- Mar 06 (2)

- Mar 05 (1)

- Mar 04 (2)

- Mar 01 (2)

- Feb 28 (4)

- Feb 27 (3)

- Feb 14 (1)

- Feb 13 (2)

- Feb 12 (2)

- Feb 08 (1)

- Feb 07 (5)

- Feb 06 (1)

- Feb 04 (2)

- Jan 31 (3)

- Jan 29 (1)

- Jan 28 (2)

- Jan 24 (1)

- Jan 23 (1)

- Jan 22 (2)

- Jan 19 (2)

- Jan 17 (7)

- Jan 16 (2)

- Jan 15 (4)

- Jan 14 (2)

- Jan 09 (1)

- Jan 02 (3)

- Dec 17 (3)

- Dec 14 (8)

- Dec 13 (11)

- Dec 12 (19)

- Dec 09 (1)

Blooming like a flower!

ENGLISH SONG

Heal The World

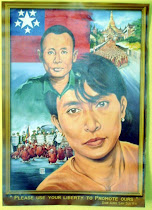

General Aung San

Ideal Hero of Myanmar

Burmese Songs

Like Father, Like Daughter

.jpg)

Comment me,please!

Music Around the World.

HelpingHands2NargisSurviors

ေတးဆို-(ေလးျဖဴ၊ မ်ဳိးႀကီး၊ ဟယ္ရီလင္း၊ ဆုန္သင္းပါရ္ႏွင့္ အျခားအဆိုေတာ္ေပါင္းမ်ားစြာ)

ျပဇာတ္တပုဒ္လို ခဏအခ်ိန္ေလးအတြင္းမွာ ငါတို႔ရဲ႕ဘ၀ေတြ အဆံုးတိုင္ ေပ်ာက္ကြယ္ၿပီလား

ႀကိဳးစားၿပီး အိုေဆာက္တည္ခဲ့သမွ်ဟာ အခုေတာ့ နံေဘးမွာ ဖိတ္စဥ္ေႂကြက်

ေရျပင္ႀကီးရဲ႕ ရက္စက္မႈမွာ အရာရာ အသစ္က စရမလား

ပိုင္ဆိုင္ခဲ့သမွ် ငါတို႔ ဘ၀ဟာ မၿမဲျခင္းတရားတဲ့လား

ဆံုး႐ံႈးခဲ့ၿပီ လူ႔အသက္ေပါင္းမ်ားစြာ မိသားစုမ်ားစြာ ႀကိတ္ခါ႐ိႈက္ငိုသံမ်ား

ႏွလံုးသားထဲမွာ ပြင့္ေ၀ဆဲေမတၱာ ေပးအပ္ဖို႔ရာ လက္ခံမယ့္သူ႐ွိမလား

အၾကင္သူမိဘ သားသမီးမ်ားစြာ ျပန္ဆံုဆည္းခြင့္ ရႏိုင္ပါ့မလား

အႏၲရာယ္ေရျပင္က်ယ္ႀကီးထဲမွာ အခ်စ္နဲ႔ဘ၀ေတြ အဆံုးတိုင္ပ်က္စီးသြား

(ဆုန္သင္းပါရ္) ျပန္လည္အစားထိုးရႏိုင္မလား ေပ်ာ္႐ႊင္စရာမိသားစု ကမၻာေလးမ်ားစြာ

(ဟယ္ရီလင္း) ဆံုး႐ံႈးေပ်ာက္ကြယ္ခ်ိန္မွာ ႏွစ္သိမ့္မႈကို ငါတို႔ေပးႏိုင္မလား

စာနာမႈနဲ႔ ေဖးကူမလား ဒီေျမေပၚ အတူႀကီးျပင္း တို႔ေသြးရင္းပါ

လက္တြဲအခုအခ်ိန္မွာ လက္ကမ္းလို႔ ကူပါ

အၾကင္နာေတြနဲ႔ ေဖးကူပါ

အေမေပ်ာက္လို႔လိုက္႐ွာ ကေလးငယ္ေပါင္းမ်ားစြာ ငိုေႂကြးလို႔ဟစ္ေအာ္

မိခင္ၾကားႏိုင္ပါ့မလား

အေျပးအလႊားလိုက္႐ွာ အေဖ့ကိုလည္း မေတြ႔ပါ ေထြးပိုက္ဖို႔ရာ ဖခင္ေကာ ျပန္လာမလား

အၾကင္သူမိဘ သားသမီးမ်ားစြာ ျပန္ဆံုဆည္းခြင့္ ရႏိုင္ပါ့မလား

မာယာအျပည့္နဲ႔ မုန္တိုင္းေအာက္မွာ တြဲလက္ျဖဳတ္ကာ အေ၀းဆံုးေ၀းခဲ့ရ

ငါ့ရဲ႕ႏႈတ္ခမ္းေတြ ရမ္းေရာင္ေျခာက္ကပ္လာ အသက္ဆက္ခြင့္ကို ရႏိုင္ပါ့မလား

အသက္ေပ်ာက္ခဲ့ၿပီ ငွက္ငယ္ေလးမ်ားမွာ ႐ုပ္၀တၳဳေတြ ေမ်ာပါျမစ္ျပင္အႏွံ႔အျပား

ေရျပင္ႀကီးရဲ႕ ရက္စက္မႈမွာ အရာရာအသစ္က စႏိုင္မလား..

သန္းေခါင္ယံညရဲ႕ ဆုေတာင္းမ်ားစြာ ျပည့္၀ခြင့္ဟာ အားလံုးရဲ႕ အေျဖလား

(အူး.. အားလံုးရဲ႕အေျဖလား)

ျပန္လည္အစားထိုးရႏိုင္မလား ေပ်ာ္႐ႊင္စရာမိသားစု ကမၻာေလးမ်ားစြာ

ဆံုး႐ံႈးေပ်ာက္ကြယ္ခ်ိန္မွာ ႏွစ္သိမ့္မႈကို ငါတို႔ေပးႏိုင္မလား

စာနာမႈနဲ႔ ေဖးကူမလား ဒီေျမေပၚ အတူႀကီးျပင္း တို႔ေသြးရင္းပါ

လက္တြဲအခုအခ်ိန္မွာ လက္ကမ္းလို႔ ကူပါ

အၾကင္နာေတြနဲ႔ ေဖးကူပါ

(ေလးျဖဴ) ဆံုး႐ံႈးခဲ့တဲ့ တို႔ဘ၀ေတြ အတူျပန္လည္တည္ေဆာက္ၾကမယ္

အေႏြးေထြးဆံုးဒီအခ်စ္မ်ားနဲ႔ အူး..

(မ်ိဳးႀကီး) ရင္ဆိုင္ၾကဖို႔ လက္ေတြ အတူ.. တြဲထား အိုး ဘ၀ေတြ

တေခါက္ျပန္လွေစဖို႔ အတူတူျဖစ္ေစရမယ္ တို႔ရဲ႕လက္မ်ားနဲ႔ (လက္မ်ားနဲ႔)

မင္း.. အခ်စ္နဲ႔လက္မ်ား ေပးလိုက္ေပါ့ ဘ၀မ်ားစြာ ႐ွင္သန္ဖို႔ အခြင့္ေတြဟာ

ကူညီသူကို ေစာင့္စား

အခ်စ္.. ကမ္းမယ့္လက္မ်ား ၀မ္းနည္းမႈ အိမ္ထဲ ေၾကကြဲ ေရထဲ

(အူး... အခ်စ္နဲ႔ဘ၀ေတြ နာၾကင္ျခင္း)

မင္း.. အခ်စ္နဲ႔လက္မ်ား ေပးလိုက္ေပါ့ ဘ၀မ်ားစြာ ႐ွင္သန္ဖို႔ အခြင့္ေတြဟာ

ကူညီသူကို ေစာင့္စား

အခ်စ္.. ကမ္းမယ့္ (တို႔လက္မ်ား) လက္မ်ား ၀မ္းနည္းမႈ အိမ္ထဲ ေၾကကြဲ ေရထဲ

နာၾကင္အေဖာ္မဲ့ ဘ၀ေတြ

Recommended Links

- 'DIARY 39'

- Ah Phong

- Ahunt Phone Myat

- Anyartharlayy

- Canada Myanmar

- CHIN MA LAY

- DREAM

- February's Notes

- First Step to Computer World

- Hinnlinnpyin

- I'm gonna miss you

- Khunmyahlaing

- Kyal Sin Nat Tha Miee

- Lin Let Kyal Sin

- My Wonderful Moral Thoughts

- MYO OO NYAN

- Oppositeyes

- REPUBLIC

- Thai-Burmese Committee for assistance to cyclone disaster victims

- U Han Gyi

- U Kalar

- Verity

- Ye Yint Nge